In the fall of 1995, I was helping the company’s IT function plan for its annual conference in March. They needed a keynote dinner speaker, and they looked to me to see if it were at all possible to get Scott Adams, creator of the Dilbert comic.

It’s hard to understand now, but the Dilbert carton was growing in popularity, and Adams – himself a former IT person – was considered the patron saint of IT. He wasn’t as well known outside of the function, not yet, anyway. But he soon would be.

How I came to be on this committee is a story in and of itself. Earlier that year, I’d asked IT for help in setting up a company web site. I was told they couldn’t help, and by the way, the web was just a flash in the pan, because the future was – I am not making this up – Lotus Notes. So, I’d gone to an outside firm.

We were a week away from launch when the company hired a new VP of IT. At his first senior staff meeting, he had everyone introduce themselves and what areas they were responsible for. When they finished the roundtable, he asked, “Who’s in charge of web development?” No one said a word, until one person volunteered, “Well, there is this guy in PR.”

I was descended upon by IT people suddenly anxious to help. I remember saying, “Please, just stay away. We’re ready to go live.”

I mention that story because it’s a Dilbert cartoon if there ever was one.

As a result, the new VP made sure I was on the planning team. And they were looking to me to see if we could get Scott Adams as the keynote dinner speaker. Everyone agreed it was a long shot.

In late October, I contacted his representative, who in turn passed me to a speaker’s bureau, which did call me back. He had had a cancellation for the time we were requesting in the spring, and he would do it. I couldn’t believe it; it had been relatively easy, and the fee was well within our budget. They faxed the contract, which I quickly signed and faxed back.

The people in IT were overjoyed. They thought I was some kind of magician, but it was really only a combination of circumstances.

Then, on Nov. 9, 1995, Bill Watterson, the creator of Calvin and Hobbes, announced he would be discontinuing the comic strip at the end of the year. As newspapers everywhere looked for a replacement, the choice was obvious – Dilbert.

Scott Adams and Dilbert suddenly rocketed to household names. At first, I worried that they might cancel, but, no, it was full steam ahead.

We arranged for transportation from the airport to the hotel, and he said he would find his way to the convention center. Dinner was at 7, and he arrived at 6:15. I met in the lobby and introduced myself. I then took him into the dinner room, where servers were still setting up. He had requested an overhead projector, and he checked the equipment and the microphone.

At dinner, he sat with the Chief Financial Officer, who was over the IT function, the VP of IT, and several other senior executives who had apparently arranged to attend the dinner to hear him, including the company’s CEO. I worried a bit about the CFO; he was a stern, dour figure, not known for having a sense of humor and often frowning at anything not connected to the business. I was sitting nearby in case of an emergency, and all seemed to go well.

As dessert was served, the chairman of the meeting introduced Scott. A senior IT manager, the man was literally bubbling with excitement. In the room were almost 500 people.

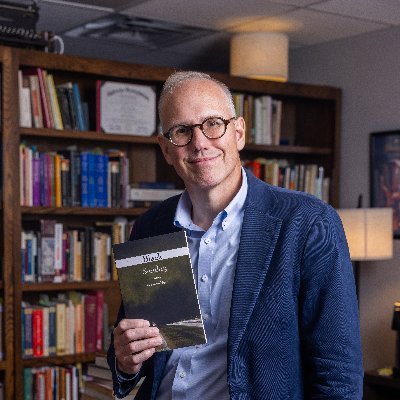

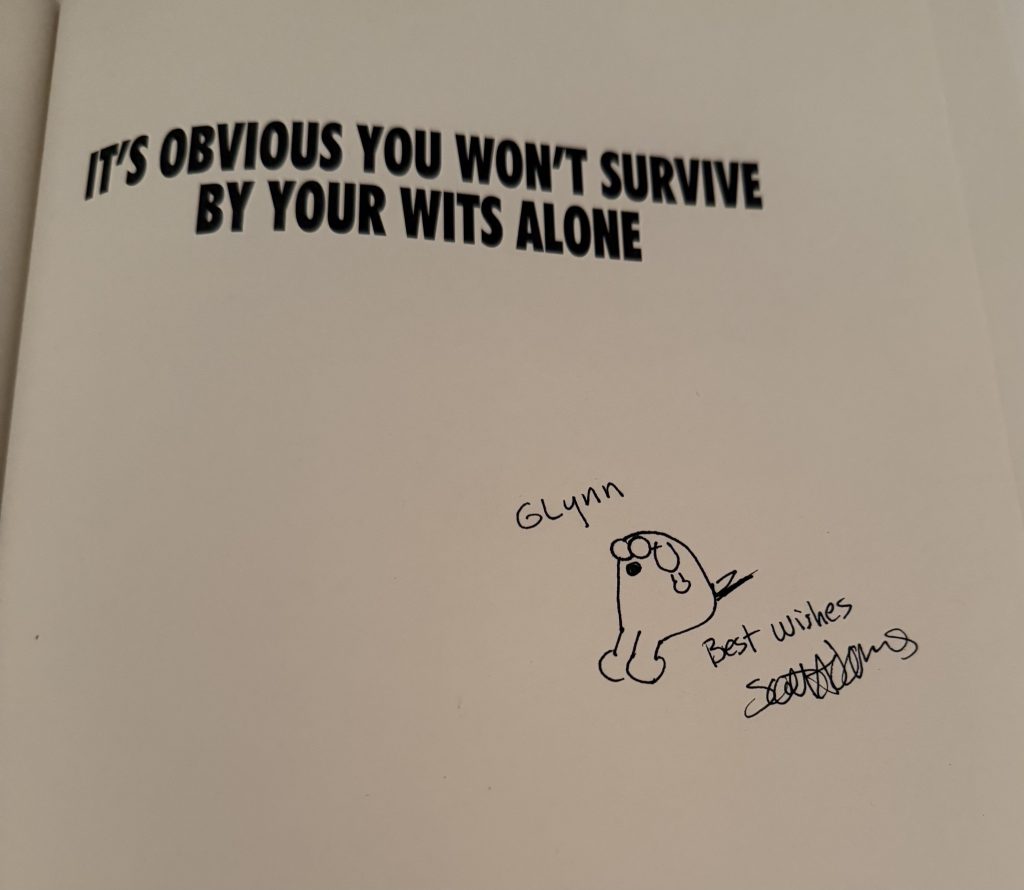

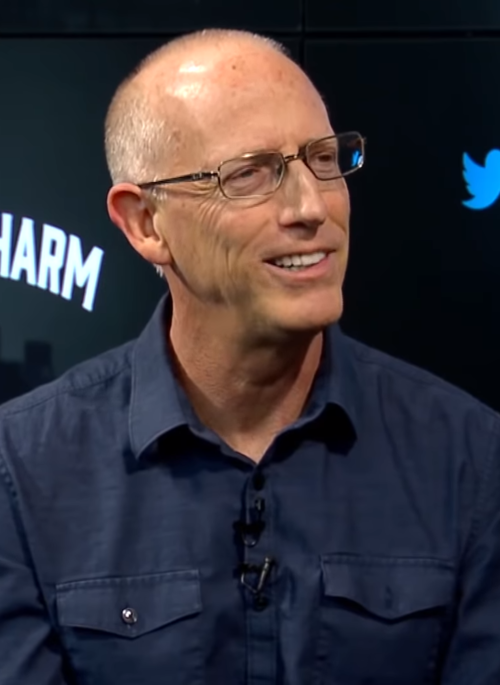

Scott’s presentation was “The Cartoon Strips That Didn’t Make It Past the Censor.” He showed the strips, telling the story associated with each one. I don’t think anyone on the room stopped laughing. The dour CFO was laughing so hard I thought he’d fall off his chair. When Scott finished, he was mobbed, and he spent at least an hour autographing Dilbert books people had brought to the speech. Including me, and you can see my personalized one above. (I still have the book.)

The CFO made a point of congratulating me for the arranging what he called “the best after-dinner speech I’ve ever heard.”

I walked him back to his hotel. We talked about Dilbert, drawing cartoons, and the presentation. He said that when Bill Watterson made his announcement, he and his cats did a conga line to celebrate. I told him that his cartoon strip had manage to capture the idiocies of corporate life (and corporate life in the 1990s was saturated with idiocies). I also said that a few months ago, I had stuck a Dilbert cartoon on the door of my office, and it had become something of a shrine, with people sticking up their favorites on the door. (HR tolerated it. Barely.)

That was Scott’s genius: He captured corporate life as millions of us were living it.

People said afterward it was the highlight of the conference. Scott Adams was the perfect speaker, and a perfect gentleman. He was funny, and he knew how to use self-deprecating humor (the only safe kind). He struck me as someone who loved his work, and he was still somewhat bewildered by what seemed like instant fame. And as the years went by, he never lost it that sense of surprise and wonder.

And now he’s gone. The creator of Dilbert, the Boss, Catbert, Dogbert, and Ratbert belongs to the ages.

Related:

Dilbert Creator Scott Adams Dies at 68 – Fox News.