My historical novel Brookhaven has no illustrations. I spent an estimated third of my research time hunting for them.

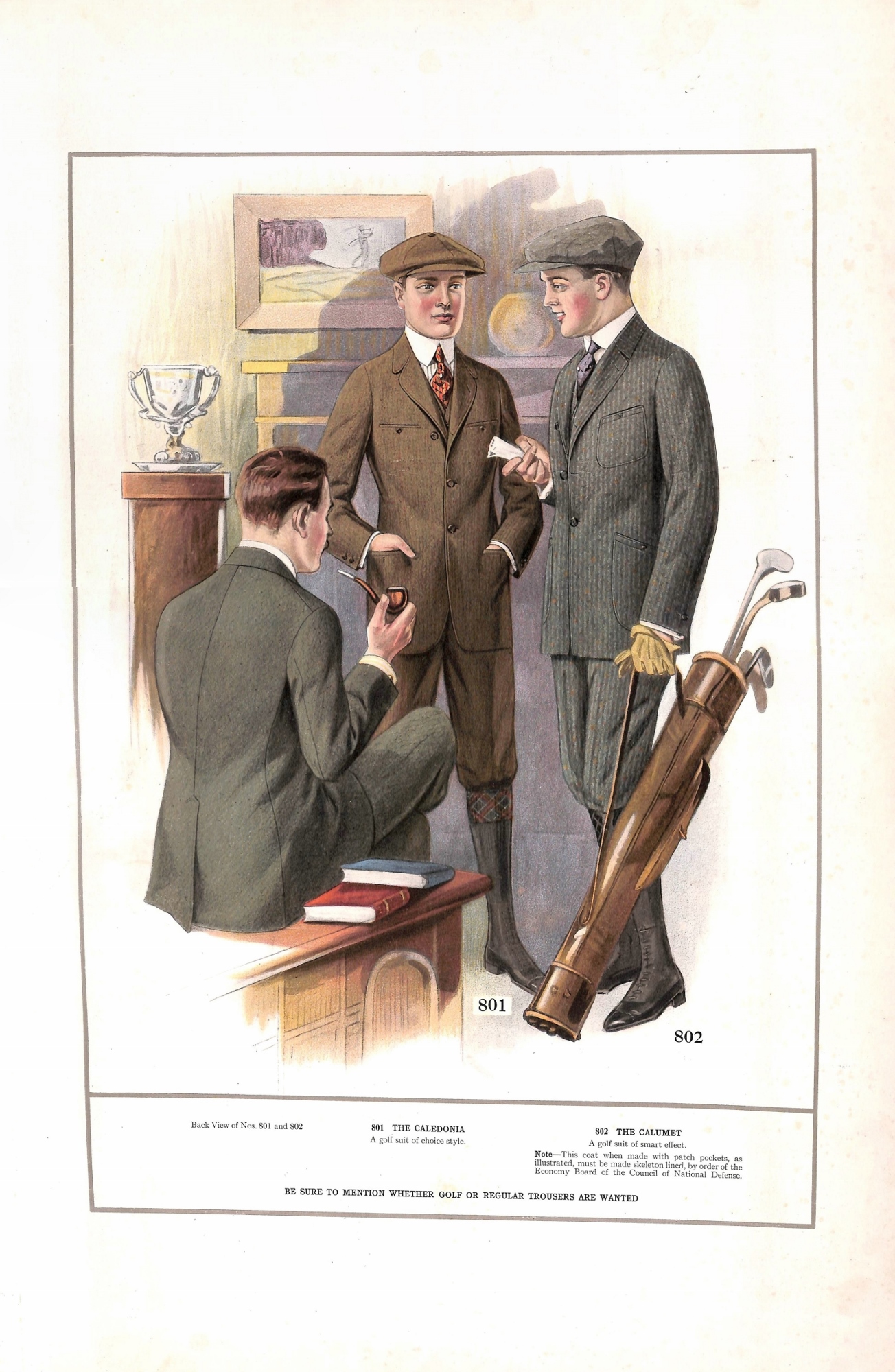

The novel is set in two different time periods – the Civil War and immediately after, and then 50 years later, in 1915. From the beginning of the first draft, I quickly learned that I had to see both periods. I had to see what people wore, what they ate, how they traveled, what their homes were like, what their streets and communities were like, and more.

From early on, I had to spend far more time looking than reading, and vastly more time looking than writing. Thos 50 years were some of the momentous in American history – rapid industrialization during the war and after, wagons and carriages giving way to automobiles, the advent of flight, the rapid spread of newspapers supported by wire services like Associated Press, rapid changes in the position of women in society, and mechanized agriculture becoming the rule rather than the exception.

To continue reading, please see my post today at the ACFW Blog.

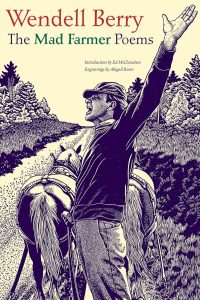

Illustration: Men’s golfing fashions in 1915.