“Well we have had a big battle where they Shot real bullets and I am safe. Except a buckshot wound in the hand and a bruised shoulder from a spent ball…” – Letter from William T. Sherman to his wife Ellen Ewing Sherman, April 11, 1862, after the Battle of Shiloh.

Growing up, I had a grandmother who referred to the Civil War as “The War of Northern Aggression” which had been won for the North by “that drunkard General Useless Grant.” Her father-in-law had been a young soldier in the war; relatives on both sides had fought and died. A century later, the Civil War was still being fought, at least when she was present, wrapped up in loss, memory, and an unshakeable belief in the “Lost Cause.”

But no Union officer received my grandmother’s opprobrium like William Tecumseh Sherman, whom I understood to be a personification of Lucifer.

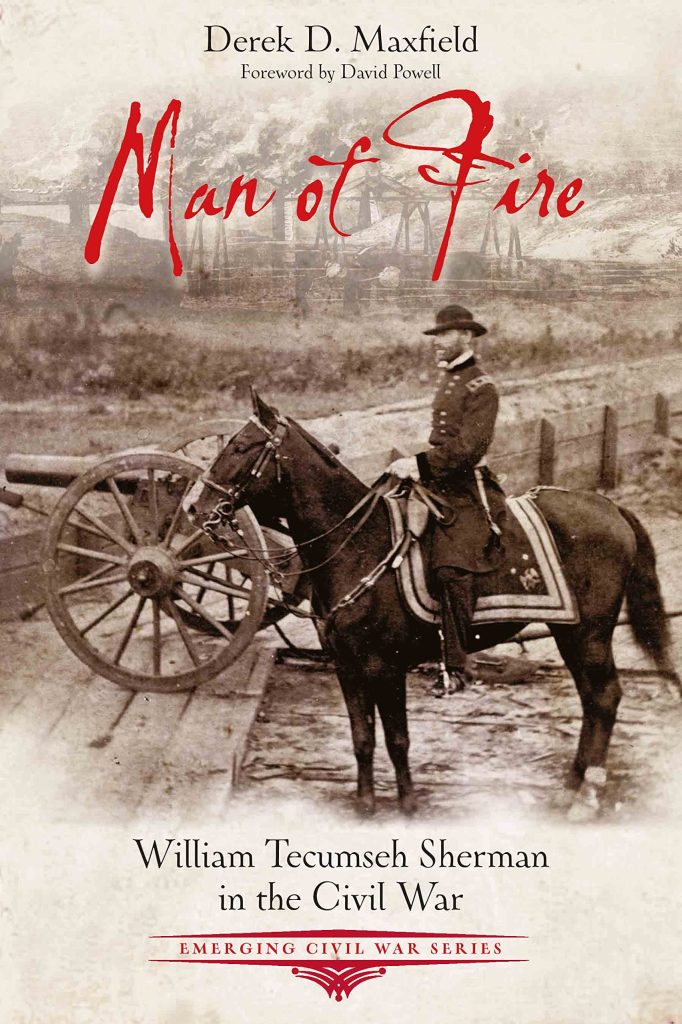

And that so-called Lucifer is the subject of Man of Fire: William Tecumseh Sherman in the Civil War, the highly readable, fact-filled, and wonderfully illustrated biography by Derek Maxfield. This is not a comprehensive, “be-all-and-end-all” study of the man; instead, it focuses on his Civil War years and military service.

The man who emerges from these pages is complex, ambitious, doubt-ridden, often depressed, and an incredibly competent and capable leader. He was lauded in the North and despised in the South and for largely the same reason: the March through Georgia in late 1864. The earlier fall of Atlanta made Sherman a Union hero (and assured Abraham Lincoln’s reelection), setting the stage for the march to the sea. Maxfield notes that many credit Sherman with inventing the idea of “total war.” It wasn’t only about defeating armies in the field but also about destroying the supply base and demoralizing the civilians. And the march did exactly that. It also became one of the major pillars of the “Lost Cause” mythology.

Man of Fire describes how Sherman, after repeated business failures in civilian life, found a natural home back in the military. But it wasn’t an easy ride. Early on, it appeared his career was over; the man likely had something like a nervous breakdown. But his service at Shiloh helped restore the luster. It also helped that Grant supported him through good times and bad.

Sherman also had to deal with Washington politics, and specifically Edwin Stanton, the Secretary of War. He may have been a military hero, lauded in the press (and Sherman knew exactly how fickle the press could be), but the general had to deal with Stanton’s interfering and eventual humiliation over the peace terms offered to Confederate Gen. Joseph Johnston. Maxfield succinctly summarizes all of this.

Maxfield is an associate professor of history at Genesee Community College in Batavia, New York, and has received several awards for teaching. He previously published Hellmira: The Union’s Most Infamous Civil War Prison Camp – Elmira, N.Y. Maxfield has also written and directed several plays, including Now We Stand by Each Other Always and Grant on the Eve of Victory. He is a lecturer on several Civil War, Victorian America, and American Revolution topics, and he’s been a regular contributor to the Emerging Civil War blog since 2015. He lives with his family in New York.

Man of Fire doesn’t tell you everything you might want to know about Sherman, but that’s not its intent. It summarizies the Civil War years, highlighting the mjnor events of the general’s military career and personal life (including the death in Memphis of his beloved son from typhoid. It gives you the general and the man, his victories and accomplishments as well as his failures. At the end, you understand William Tecumseh Sherman better than you did when you started to read it.

But I can still see my grandmother shaking her finger at me.

Top illustration: What the black-and-white photographs of the era don’t pay justice to is Sherman’s red hair.