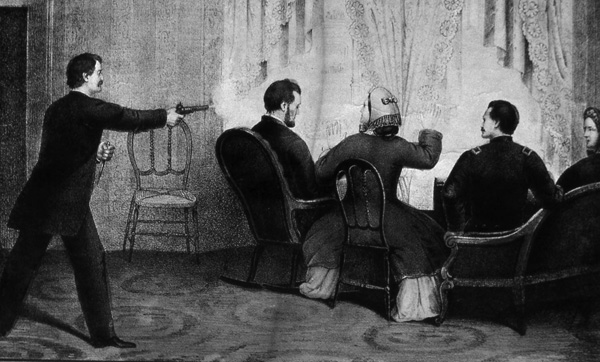

Less than week after Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S Grant at Appomattox, President Abraham Lincoln was shot at Ford Theatre in Washington, D.C., and died at 7 a.m. the next morning. He and his wife Mary Todd Lincoln had been watching the play Our American Cousin, a lighthearted farce about an American rube visiting his aristocratic English relatives.

The Civil War was not yet over, but the end was near. As the news of the assassination spread, jubilation in the North quickly gave way to shock and anger. In the South, the news was greeted by some with enthusiasm, but by other, more prescient people, with trepidation. Lincoln’s death would not bode well for the South.

Harold Holzer, one of the leading authorities in the United States on Lincoln and the era, considered the first-hand accounts – diaries, letters, newspaper editorials, official announcements, testimonies, affidavits, speeches, and more. (It surprises us today that the reports took weeks to reach the broad mass of people North and South). He then collected some of the best and assembled President Lincoln Assassinated!! The Firsthand Story of the Murder, Manhunt, Trial, and Mourning.

What a treasure this is. We can read the reactions and responses of people from all walks of life, North and South, to the news of the President’s murder. The first report by the Associated Press. Letters by Edwin Stanton, Secretary of War. Eyewitness accounts of what happened at the theater. Letters written to U.S. diplomats. Fanny Seward’s account of the attack on her father William Seward and her brother in their home. (The Secretary of State was recovering from a carriage accident; the neck brace he had to wear likely saved his life from the knife-wielding assailant.) Entries from John Wilkes Booth’s diary, written as the authorities closed in.

We follow events from shortly before the attack in Ford’s Theatre, through the death and funeral procession to Springfield, Illinois, and then to how Lincoln and the assassination began in live in American memory.

As the attack on Seward makes clear, the assassination was indeed a conspiracy. The idea was to kill leading figures in the federal government, throwing the government into chaos and gaining revenge for the South. Ulysses Grant and his wife Julia were supposed to have joined the Lincolns in the box at Ford’s theatre, but Grant knew full well that his wife and Mary Lincoln did not get along; Grant found an excuse to be absent. Booth was eventually found and shot; four others were convicted, including Mary Surratt, the first woman to be executed by the federal government.

Holzer has written, edited, or co-authored more than 40 books on Lincoln, the Civil War era, and related subjects. From 2010 to 2016, he served as chairman of the Lincoln Bicentennial Foundation, having previously co-chaired the U.S. Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission. He received the National Humanities Medal in 2008. He is currently the chairman of The Lincoln Forum.

President Lincoln Assassinated!! is an excellent collection of first-hand accounts of Lincoln’s death and the aftermath. It provides the opportunity to go behind the historical summaries and see the emotion, the horror, and the shock expressed by Americans when they first heard the news, and what they saw and experienced first-hand.

Top illustration: A depiction of the shooting at Ford’s Theatre.