If there is a state we most associate with the American Civil War, it is Virginia. Numerous battles occurred there; the federal and confederate armies faced each other for four years, most often in a stalemate; and the two enemy capitals ensured that Virginia was a major theater of the war. And it was in Virginia that Robert E. Lee ultimately surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant.

Some have argued that the United States really won the war farther west – the fall of New Orleans and Vicksburg, the battles around Nashville and Chattanooga, the capture of Atlanta in 1864, and Sherman’s March to the Sea.

And then there was Mississippi, the second state (after South Carolina) to secede from the Union. The Civil War in Mississippi was more – far more – than Vicksburg. Historian Michael Ballard (1946-2016) tells the story in The Civil War in Mississippi: Major Campaigns and Battles (2011). The book is volume 5 of the Heritage of Mississippi published by the University Press of Mississippi for the Mississippi Historical Society and the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

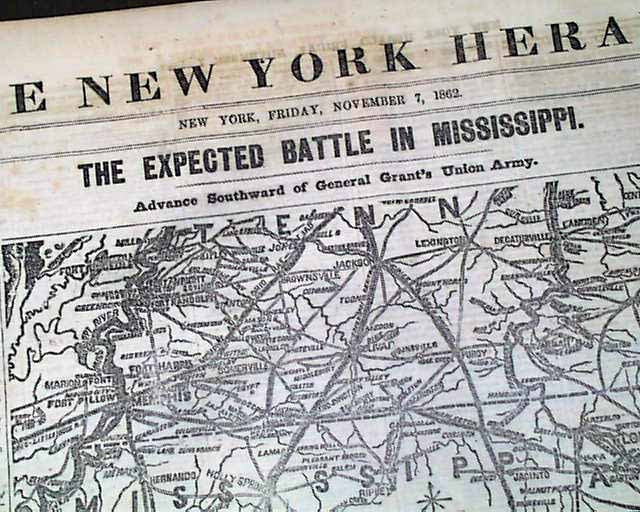

Vicksburg (1863) may have been the most important battle in the state; its surrender solidified control of the Mississippi River by the United States and severed the Confederacy in half. But the northern part of the experienced numerous battles. The town of Holly Springs changed hands 57 times. The town of Oxford was burned. The state capital of Jackson fell twice to the federals; Grant took the city and then attacked Vicksburg from the east. Before he marched to the sea in Georgia, Sherman marched from Jackson to Meridian in similar fashion, destroying anything that might be of value to the Confederates. Major Benjamin Grierson led a three-week-long raid with 1,700 cavalry troops from the Tennessee line south, eventually arriving in federally held Baton Rouge in Louisiana.

The destruction through the years of war was large-scale – plantations, factories, warehouses full of supplies, railroad deports and track, and whole towns in some cases. In his well-written and highly readable account, Ballard succinctly tells the story of all of what happened.

During his lifetime, Ballard published numerous books about the Civil War, including A Long Shadow: Jefferson Davis and the Final Days of the Confederacy (1986); Landscapes of Battle: The Civil War (1988); Pemberton: The General Who Lost Vicksburg (1999); A Mississippi Rebel in the Army of Northern Virginia: The Memoirs of Private David Holt (1995); Grant at Vicksburg: The General and the Siege (2003); U.S. Grant: The Making of a General 1861-1863 (2005); and several others. He received his B.A., M.A., and Ph.D. degrees from Mississippi State University, where he also worked as archivist and director of the Congressional and Political Collection.

The Civil War in Mississippi is a fine history and a sobering one. By the end of Civil War, the state’s economy was in ruins, its towns and cities had experienced widespread destruction, thousands of its men had died on battlefields across the state and the South, and its social order was turned upside down. Recovery would be a long time coming.

Top photograph: Artist’s rendering of the Battle of Corinth, Miss.; Mississippi Department of Archives and History.