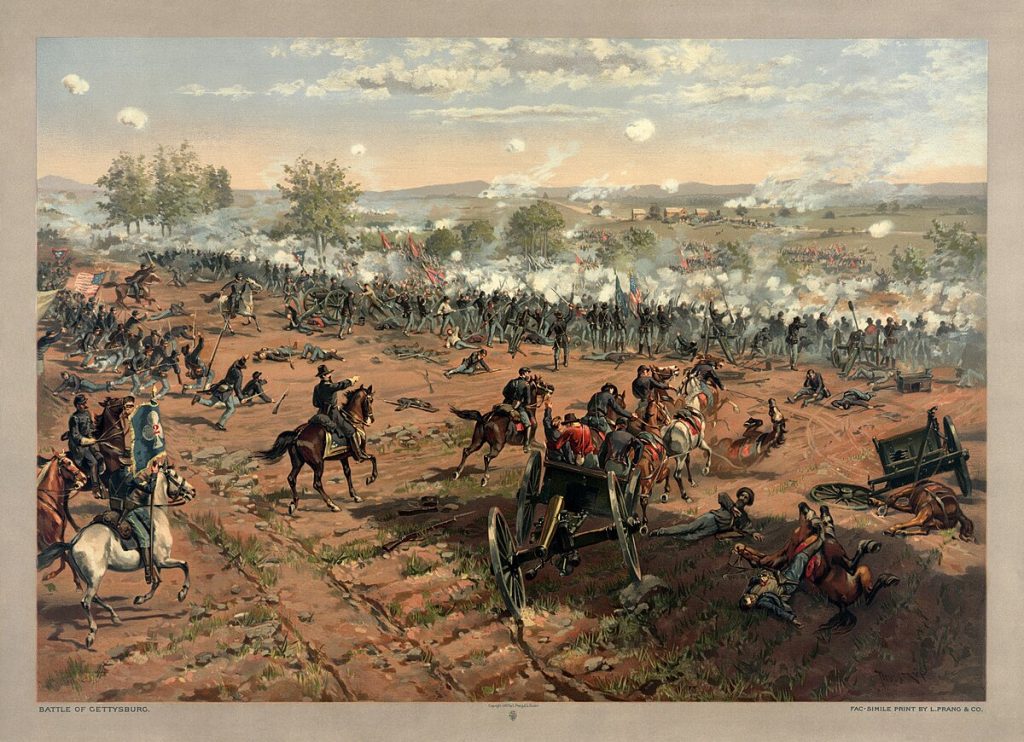

A considerable portion of my historical novel Brookhaven is set in the last year of the Civil War, and yet the novel only covers a few of the momentous events – the battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Courthouse, the final siege of Petersburg, Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox, and Johnston’s surrender to Sherman near Greensboro.

Indirectly, the novel covers Grierson’s Raid through Alabama, the fall of Atlanta and Sherman’s march to the sea, and the political and social chaos that followed. People lived through those times; my own ancestors (on both sides of my family) lived through it.

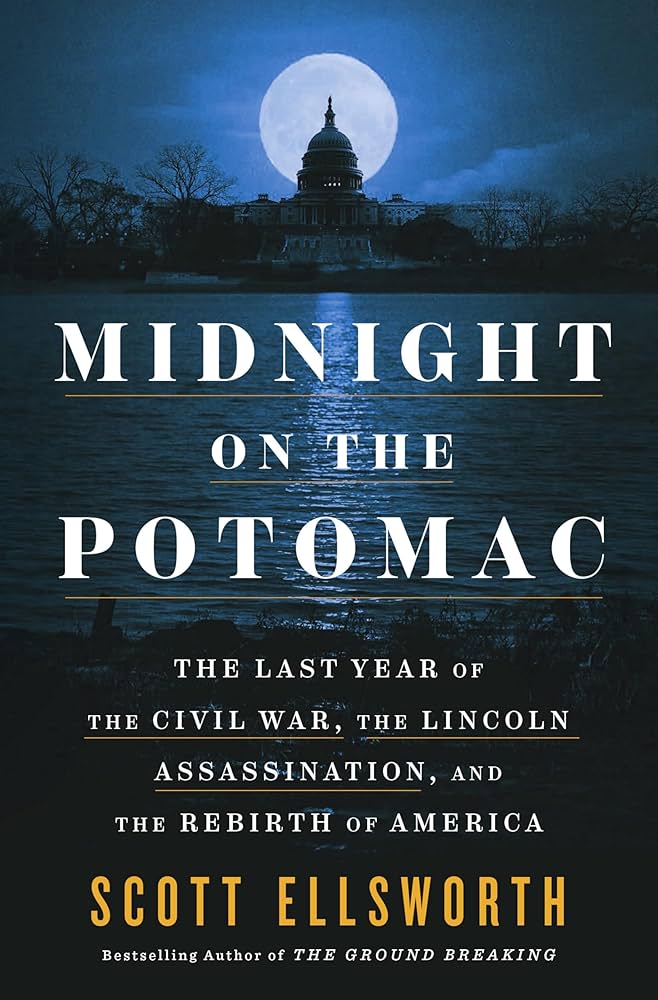

The last year of the Civil War is also the focus of Midnight on the Potomac: The Last Year of the Civil War, the Lincoln Assassination, and the Rebirth of America. In almost a conversational vignette style, historian Scott Ellsworth guides the reader through the major events of 1864-1865, showing how they not only were significant in and of themselves but also how they shaped post-war America.

You meet spies and ghost armies, experience the horrific battle in the Wilderness near Richmond, and discover how slaves were liberated and sometimes abandoned by Union armies. You follow the acting career of John Wilkes Booth and how it led to that fateful night at Ford’s Theater. You learn how the fall of Atlanta assured Lincon’s reelection, and you join Booth in listening to Lincoln’s second inaugural speech. You meet the famous and not-so-famous, and you experience history in many of the words and first-hand accounts of the people who were themselves involved.

It says something of Ellsworth’s skill that the writing and stories seem almost effortless. You know they’re not; a prodigious amount of research and knowledge was required for that “effortlessness.”

Ellsworth previously published The Ground Breaking: The Tulsa Race Massacre and an American City’s Search for Justice; Death in a Promised Land: The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921; The Secret Game: A Wartime Story of Courage, Change, and Basketball’s Lost Triumph; and The World Beneath Their Feet: Mountaineering, Madness, and the Deadly Race to Summit the Himalayas. He attended Reed College in Oregon and graduate school at Duke University in North Carolina. And he also worked as a historian at the Smithsonian Institution. He lives with his family in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and he teaches at the University of Michigan.

Through the power of stories, Midnight on the Potomac explains what happened that last, fateful year of the Civil War, and it does so in a highly readable, engaging way.