In high school and college, when we read about or study the American Civil War, we learn primarily about the political and military figures and the battles and campaigns. When I attended LSU, the school’s history department had a national reputation, with professors like T. Harry Williams, who was not only a highly regarded Civil War historian but also wrote the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Huey Long. Williams published several books on Abraham Lincoln, P.G.T. Beauregard, Civil War generals, and related topics.

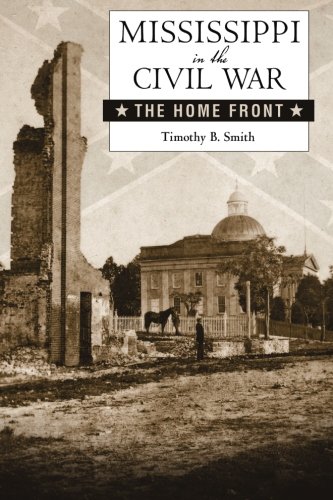

In recent years, more attention has been paid to the war and how it affected civilians. When Union armies invaded the Southern states, they civilians they encountered were largely women, children, and older men beyond military age. And it is this group, and their lives in towns, cities, and farms, that Timothy Smith considers in Mississippi in the Civil War: The Home Front.

Smith divides his story in two pieces. First is how the state of Mississippi dealt with the military conflict from secession through the end of the war. The second is how the civilian population experienced the war. He pays particular attention to the belief among historians that the South was defeated not only by Northern industrial might but also by the people losing the will to fight. He finds some of that may be true, but that the “losing the will to fight” sentiment may have played a smaller role than previously thought.

Mississippi’s surely had more than sufficient reason to lose heart. From early in the war, the state was devastated economically, militarily, and socially. Agriculture was disrupted, cities burned, and railroads destroyed. What little there was industrial infrastructure also suffered severely. Deserters and criminals freed from jails roamed the countryside. Cotton, which had been the state’s primary crop, became almost useless with the federal blockade of ports. Inflation soared. Foodstuffs became scarce. The state had to sequester food for the military. Many people fled the state during the war for less affected places like Texas. (My own Mississippi ancestors did precisely that, returning only after the war was over.)

Particularly interesting is Smith’s discussion of the anti-secession sentiment in the state, which was surprisingly strong. Not everyone wanted to leave the Union; not everyone owned slaves. But everyone would largely suffer equally.

Smith provides an overview of what people experienced. Military battles aside, it was a dark time for many people in the South, free and slave, and the effects would be felt for decades. Some say the effects are still being felt.

Smith’s numerous books on the Civil War include accounts of the battles of Vicksburg, Corinth, Champion Hill, Shiloh, Forts Henry and Donelson, and Chickamauga; the Mississippi secession convention; U.S. Grant’s invasion of Tennessee; and the Grierson Raid in Mississippi. A professor of history at the University of Tennessee at Martin, he’s won numerous awards for his books, including the Fletcher Pratt Award, the McLemore Prize, the Richard Harwell Award, the Tennessee History Book Award, the Emerging Civil War Book Award, and the Douglas Southall Freeman Award. He lives with his family in Tennessee.

Mississippi in the Civil War: The Home Front is a sobering story. Mississippi and the other Southern states may have brought the war upon themselves, but its people endured and survived, Smith explains how that happened.

Related:

“The Real Horse Soldiers” by Timothy Smith.

Top photograph: The original Oxford, Miss., courthouse, with a Union army encampment on its grounds.