My introduction to series fiction happened in college. I was checking the sale table at a B. Dalton’s Bookstore and found God is an Englishman by R.F. Delderfield, a novel about the Swann family set in mid-19thcentury England. Not long after, I realized there was a second volume, entitled Theirs Was the Kingdom. And a couple of years later, the third and final volume, Give Us This Day, in the series was published.

I loved those stories. Delderfield had created an entire world built around the coming of the railroads and how one man realized that there was opportunity in the routes not connected by the railroads. He builds a business empire upon that realization. It was (and is) good, old-fashioned storytelling at its best. I still have those three books.

Writing a fiction series seems to have become popular in the 19thcentury. It’s not the same thing as serial publication, which is how Charles Dickens published his novels – a chapter per issue of a periodical. One of the best-known series in the 19thcentury was the Chronicles of Barsetshire by Anthony Trollope, comprised of six related novels. Trollope also write the six-volume Palliser series.

Writing a fiction series seems to have become popular in the 19thcentury. It’s not the same thing as serial publication, which is how Charles Dickens published his novels – a chapter per issue of a periodical. One of the best-known series in the 19thcentury was the Chronicles of Barsetshire by Anthony Trollope, comprised of six related novels. Trollope also write the six-volume Palliser series.

The currently popular Poldark television program on PBS is based on the 12 novels written by Winston Graham, written in two periods, four from 1945 to 1953 and the rest from 1973 to 2002. And a beloved series still being published are the Mitford novels of Jan Karon.

Fiction series are not limited to adults; in anything, they’re even more popular among children. I grew up on the Hardy Boys. Other popular children’s series at the time were Nancy Drew, The Dana Sisters, the Bobbsey Twins, Trixie Belden, and others. Today, my 8-year-old grandson is deep into the Boxcar Children series.

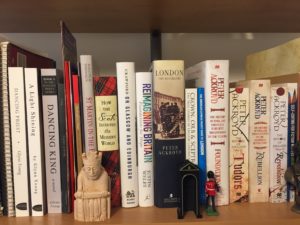

Having written three novels in a series, with the fourth now in editorial production, I can explain why fiction authors tend to write related books. Dancing Priest began its manuscript life as some 250,000 words, almost enough for three novels. (For a word-count comparison, War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy is 587,000 words.) (Tolstoy could get away with that. Few if any novelists could get away with that today.) I ended up splicing it into a novel of 92,000 words, a manuscript of 70,000 words that was eventually expanded to become A Light Shining, a manuscript (a really rough manuscript) of 45,000 that grew to become Dancing King, and some 35,000 words that eventually made their way into the fourth novel in the series, tentatively entitled Dancing Prophet.

What happened was this: as I constructed what became the world of Michael and Sarah Kent-Hughes, the construction grew, it expanded over time, it became more elaborate and detailed, and it became too big to be contained in only a single book. What was one rather large manuscript was transformed into four novels.

What happened was this: as I constructed what became the world of Michael and Sarah Kent-Hughes, the construction grew, it expanded over time, it became more elaborate and detailed, and it became too big to be contained in only a single book. What was one rather large manuscript was transformed into four novels.

There are potentially more. I have story ideas and even extended fragments and outlines for additional books. I’m not sure if I will go there, although it’s difficult to resist when you’ve connected with a character who won’t appear for another two or three books. Perhaps what will happen, or what should happen, is that these fragments and outlines will make it into a story collection.

But I know what it is for an author to publish a series. You come to inhabit a fictional world, one of your own creation. It becomes incredibly familiar. You see things in the real world and almost without thinking apply them to your fictional world. You read a newspaper story and translate it to your fictional world. Sometimes you get surprised and discover that something you wrote becomes reality. That’s happened to me at least three times during the writing of the Dancing Priest novels.

Little did I know when I picked up that copy of God is an Englishman.

Top photograph by Jake Hills via Unsplash. Used with permission.

The kidnapper was a man named

The kidnapper was a man named  In 2012, in a conversation with my publisher about writing life after A Light Shining, I mentioned this story. A few days later, he sent me a press story from England. A small pedophile ring had been uncovered within the Church of England. He wanted to know if I had “pre-written history.”

In 2012, in a conversation with my publisher about writing life after A Light Shining, I mentioned this story. A few days later, he sent me a press story from England. A small pedophile ring had been uncovered within the Church of England. He wanted to know if I had “pre-written history.”

The manuscript carcass – what was left over – had piled up. The publisher suggested a sequel. Out came the metaphorical ax again and chopped off about 65,000 words. Because of changes in Dancing Priest during the rewriting and editing process, those 65,000 words had to be reworked even more than the first manuscript. The story grew.

The manuscript carcass – what was left over – had piled up. The publisher suggested a sequel. Out came the metaphorical ax again and chopped off about 65,000 words. Because of changes in Dancing Priest during the rewriting and editing process, those 65,000 words had to be reworked even more than the first manuscript. The story grew. So

So