When you visit London, especially for the first time or two, two great churches are on the must-see list – St. Paul’s Cathedral and Westminster Abbey. And with good reason. Both churches are known for their soaring architecture, structural beauty, and the fact they are filled with English and British history. Right down Victoria Street form Westminster Abbey is another monumental church – the Roman Catholic Westminster Cathedral. London is a big city with big cathedral churches.

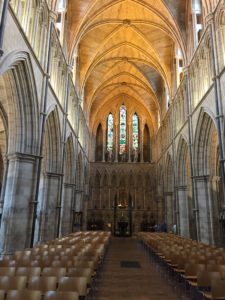

Southwark Cathedral is another church, smaller than its more famous London relatives. But of all the churches and cathedrals I’ve seen in London and England, it may be my favorite. Size has something to do with it – it’s smaller, more human-scale, still impressive, but the human eye can take it in without being completely overwhelmed.

It’s not as well known for tourists. It’s partially location – on the South Bank near London Bridge tube and train station, it’s about a half-mile walk to the Globe Theatre and Tate Modern art museum. It’s only about two blocks from the London Bridge Experience, whose replicated blood and gore I’ve so far managed to miss. The cathedral is also adjacent (about as adjacent as you can get) to the Borough Market, full of produce, stands, food shops, and restaurants and also the site of a terrorist attack in June of 2017 (not to be confused with the Westminster Bridge attack in March of 2017).

Southwark’s official name is “the Cathedral and Collegiate Church of St. Saviour and St. Mary Overie,” the “overie” meaning “over the river.” A church has existed on the site since the 7th century; archaeologists have identified the foundations of an Anglo-Saxon church there. It’s believed to have first been connected to a community of nuns, and later a community of priests. The first written reference to it is in the Domesday Book of 1086, William the Conqueror’s detailed assessment of land and resources.

In 1106, the church was reestablished as a priory and followed the Rule of St. Augustine. It was then that the church was dedicated to St. Mary Over the River. A hospital was established as well, and it would eventually grow and be transferred to what is now St. Thomas Hospital near Westminster Bridge and across the Thames from Parliament. (Incorporated into St. Thomas Hospital was the old Guys Hospital near Southwark Cathedral, where the poet John Keats studied to be a doctor.)

Southwark was the staging area for pilgrimages to Canterbury, and it was in this area that Geoffrey Chaucer launched the pilgrimage made famous in The Canterbury Tales.

The order at Southwark was dissolved along with orders across England by Henry VIII in 1539, part of the English Reformation and likely inspired by Henry’s desire to get his hands on the churches’ and orders’ prodigious wealth. The building was rented to the congregation and called St. Saviour’s; in 1611, the congregation purchased the church from James I. One of the notables buried in the church is William Shakespeare’s younger brother Edmond (1607).

The church officially became “Southwark Cathedral” in 1905. Today, the Diocese of Southwark encompasses a rather large area (and includes Lambeth Palace, the home of the Archbishop of Canterbury). It covers 2.5 million people and more than 300 church parishes.

In Dancing King, Southwark Cathedral is the place where Michael Kent-Hughes begins his series of sermons at London churches, two days before Christmas Eve. The photograph here of the nave is the view Michael would have as he’s speaking to a packed church. And it is here, the next night, where almost 1,200 people will show up for a Bible study, filling the church past overflowing, beginning what will become a religious revival in the Church of England. But it will be a revival matched by intense opposition from the senior church hierarchy.

If you visit the cathedral (and it’s well worth a visit), the entry fee is a pound (a bargain compared to the big churches). You pay your fee in the gift shop, where in return you’re given a cathedral guide. You also usually warned to make sure your guide is visible when you enter the church; one of the church wardens will politely ask to see it or send you to the shop to buy one if you don’t have it. The fee doesn’t apply during church services.

Top photograph: a view of Southwark Cathedral, with one of London’s tallest office buildings, known as “The Shard,” in the background.

Michael explains to the protestors what acceding to this demand would mean – that they would be acknowledging him as the head of all religions in Britain, including Islam, and their clergy would serve at his pleasure. They’re horrified – that isn’t what they thought their demand was about.

Michael explains to the protestors what acceding to this demand would mean – that they would be acknowledging him as the head of all religions in Britain, including Islam, and their clergy would serve at his pleasure. They’re horrified – that isn’t what they thought their demand was about.