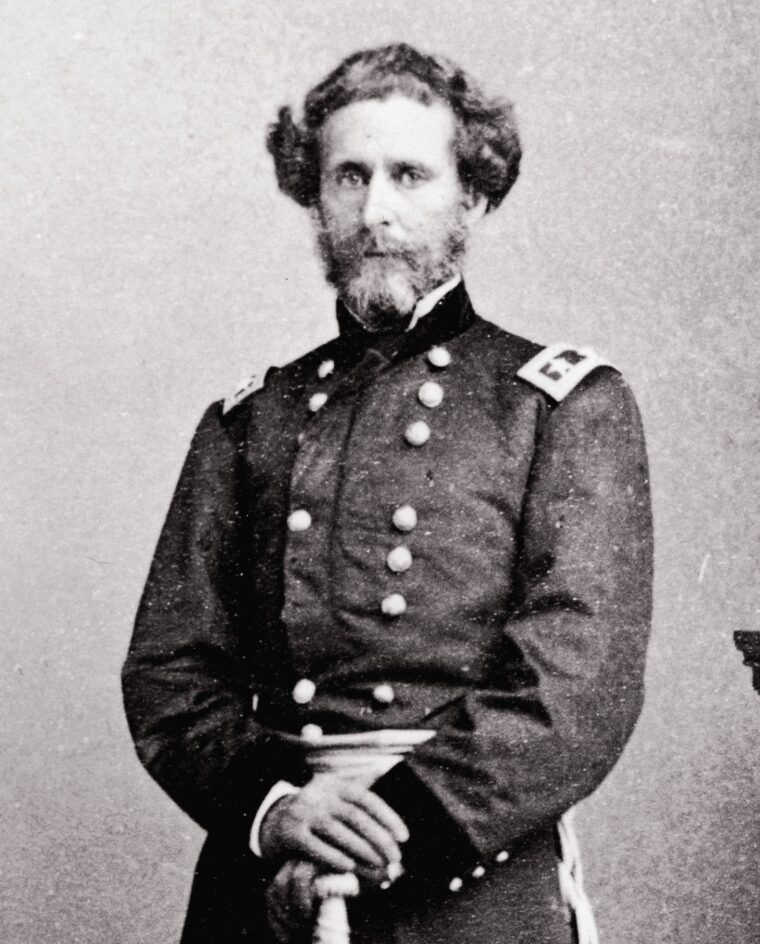

The name John Fremont (1813-1890) evokes images of Manifest Destiny, exploration of the western United States, the first Republican candidate for President (18560, and the separation of California from Mexico. Less well-known is his very brief role in the American Civil War.

For slightly more than three months in 1861, he was the commander of the U.S. Army’s Western Department, stretching from Illinois to the Rocky Mountains and headquartered in St. Louis. Those three months are now detailed in John Fremont’s 100 Days: Clashes and Convictions in Civil War Missouri by Gregory Wolk and published by the Missouri Historical Society.

Wolk has a gift. He meticulously documents the 100 days of Fremont’s office, but he tells it in a storytelling way. This isn’t some dry account of dates, names, and events, but a critical time in American history brought to life.

Fremont was appointed by President Lincoln, and almost from the beginning the man faced political opposition that only grew, particularly from the influential brothers Frank and Montgomery Blair, who had strong St. Louis ties and interests and their own preferences for military leadership in the region.

As Wolk points out, Fremont often didn’t help his own cause. He received his appointment while he was in Europe. He quickly returned to New York but waited there for the arrival of his wife Jessie and their children from California (via a rail crossing in the Panama isthmus. He likely waited far too long for a President and politicians who wanted quick action.

Once he reached St. Louis, he faced a deteriorating military situation – secessionist unrest in the northeast and southeast parts of the state (Missouri was a border slave state with a governor who almost succeeded in moving Missouri into the Confederacy), the pro-Confederacy State Guard, and Confederate forces moving up from Arkansas. The Battle of Wilson’s Creek, south of Springfield, occurred in this period, a defeat for Union forces. Critics believed Fremont had authorized too little and too late. Wolk does not that it was this battle that likely gave birth to the profession of war correspondent, with a reporter publishing the story and being almost inundated with contract offers and competitors.

Wolk includes vignettes about some of the key players, including Fremont’s wife, Jessie Benton Fremont, daughter of Thomas Hart Benton and a force in her own right. She took her husband’s defense directly to Lincoln (the meeting didn’t go well) and was his public relations manager (long before the term was invented), defender, and chronicler. Also noted is one of the early involvements in the war by an officer named Ulysses S. Grant.

Wolk is a retired attorney, previously general counsel of Three Rivers Systems, Inc., a St. Louis-based developer of academic management software. He has been executive director of Missouri’s Civil War Heritage Foundation, a program coordinator for the Missouri Humanities Council, and currently a member of the board of directors of the National US Grant Trail Association. He previously published Friend and Foe Alike: A Tour Guide of Missouri’s Civil War (2010), which describes the 237 Civil War sites in the state. He lives with his family in Webster Groves in suburban St. Louis.

In John Fremont’s 100 Days, Wolk tells a great story. Fremont emerges as a leader who made mostly political mistakes, who didn’t perceive the Administration forces growing against him. The book also conveys the sense of one of the key reasons the North appeared to be on the road to ultimate defeat – too many politicians trying to fight battles and second-guessing from the safety of their offices in Washington, D.C.

Related:

Kirkwood’s Grant Historian – Webster-Kirkwood Times.

Leave a Reply