I was struggling while I was writing the manuscript of what would become Brookhaven. I was up to my eyeballs in research; I had the overall story arc in my head. I knew it would be 1915, and the character of Sam McClure would be explaining his life during the Civil War.

I had one problem.

What would he be telling the story in the first place? Why would he be recounting both what he had previously told his family and what he hadn’t told them? I knew that in the 1890-1920 period, memoirs of the Civil War were a major genre of autobiography, but this wasn’t a case of Sam writing his story or dictating his story for it to be published as a memoir. The whole idea was him to tell the story not as it happened or chronologically, but how different events of the war shaped the rest of his life.

Bah, humbug.

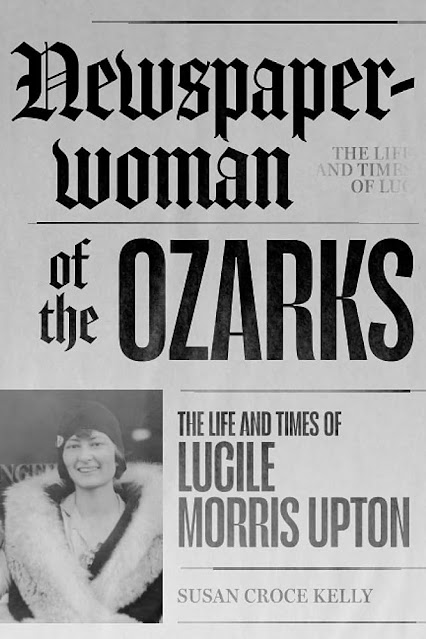

I happened to be reading a biography of a woman journalist. Entitled Newspaperwoman of the Ozarks: The Life and Times of Lucile Morris Upton, it has been written by Susan Croce Kelly, herself a former journalist at the now-shuttered St. Louis Globe-Democrat.

Susan and I had met (I can’t believe it’s been this long) some 45years ago, when we both worked in public relations. In fact, we were in the same speechwriting department for a few years. Another speechwriter in the group named Jim Fullinwider and I had lived through a book she was writing at the time, Route 66: The Highway and Its People. She used weekends and vacation time to travel the length of the old Route 66, at least where it still existed.

The highway started in Chicago and end in Los Angeles, and it was the stuff of legends. It still is today. Jim and I would sit in Susan’s office on Monday mornings, listening in wonder as she told of her weekend Interviews. She’s a born storyteller, and she was telling us stories that we and most other people had never heard before. In 2014, she published her second book, Father of Route 66: The Story of Cy Avery.

As I was struggling with myself over my own novel, I glanced at the cover of her Lucile Upton book. And I thought. If I went back about a decade in time from the photo of Lucile Upton, I would see the fashions of 1915. (I can’t explain why that thought occurred; it just did.)

Eureka! That was it. Sam McClure would be telling his story, shrouded in mystery still unsolved 50 years after the war had ended, to a newspaperwoman. And her story would turn out to be entangled with his.

Elizabeth Putnam was born. Headstrong journalist, determined to make her way in what had been a man’s world, not intimidated by what others thought, passionate about women’s right to vote as a first step, and hoping to be sent by her New York newspaper to cover the Great War in Europe.

That’s when I rewrote the beginning of Brookhaven. And that’s when I started rewriting the entire manuscript. Because Brookhaven was never meant to be a story of only the Civil War; it was the story of how a war changed lives and a culture, and how it continued to do that.

You might say I owe Lucile Morris Upton and Susan Kelly a debt of gratitude. They both helped me tell a story.

Related:

Newspaperwoman of the Ozarks by Susan Kelly.

Top photograph: Lucile Morris Upton about 1915. She would be about six years younger than the character of Elizabeth Putnam in Brookhaven.