We writers would all love to be Stephen King, James Patterson, J.K. Rowlings, and other successful people who turn everything to gold simply by their touch. For most of us, writing is difficult, frustrating, depressing, discouraging, and lacking any kind of return even remotely like the effort we put into our work. We pour ourselves into what we write, often for a very long time, and once it sees the light of day, the world yawns and moves on to books that are badly written, semi- (or totally) pornographic, or so lacking in anything of value that we wonder why we continue to do what we do.

Writing can be a slog. For most of us, writing is a slog.

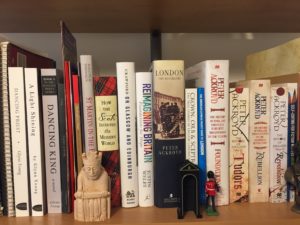

A scene inDancing King unintentionally speaks to writers, what we write, our platforms (or lack thereof), and the whole question of “why do we write.” I wasn’t thinking of writers when I wrote it, but I believe it applies to what we writers try to do.

It’s two days before Christmas. Michael Kent-Hughes flies from Scotland, where he’s on holiday with his family, to London. He’s giving the first in a series of sermons on the need to reform the church, and he’s at Southwark Cathedral. It’s an old church, dating back to early Anglo-Saxon times, but it’s a church that has managed to flourish. (Southwark is an overlooked gem for tourists, likely overshadowed by its much larger and better-known brethren like Westminster Abbey and St. Paul’s Cathedral.)

Michael gives the sermon. He has friends and staffers visiting among the 400 people in the congregation – his chief of staff, his communications leader, and his security people. People are taken aback, first by the fact of the king giving the regular Sunday sermon, and second, by what he says and how he says it. Jay Lanham, Michael’s communications man, is narrating what is happening. And he learns that Michael is speaking with an authority that seems to come from outside him. Lanham’s there in his communications capacity; he’s what might be called a “cultural Christian.” He can recall the order of the worship service from his childhood, but he finds himself overwhelmed by the truth he hears in the sermon.

Michael gives the sermon. He has friends and staffers visiting among the 400 people in the congregation – his chief of staff, his communications leader, and his security people. People are taken aback, first by the fact of the king giving the regular Sunday sermon, and second, by what he says and how he says it. Jay Lanham, Michael’s communications man, is narrating what is happening. And he learns that Michael is speaking with an authority that seems to come from outside him. Lanham’s there in his communications capacity; he’s what might be called a “cultural Christian.” He can recall the order of the worship service from his childhood, but he finds himself overwhelmed by the truth he hears in the sermon.

Afterward, Michael treats the staff people in attendance to lunch at a nearby pub. His chief of staff, Josh Gittings, asks him if he has any expectations as to how many people might attend the Bible study the next evening being organized by the church, which Michael had just encouraged the congregation to attend.

“I don’t know, Joshua,” Michael says. “And the number doesn’t matter. God can do wonders with one or two just as easily as 400.”

The response will actually be something a bit more than one or two; Michael’s sermon will spark something of a revival in the diocese. But Michael knows that this is less about what he says and how many may or may not respond, and more about what God puts in people’s hearts. Michael is a vessel; he’s not what pours into and out of the vessel.

That is the “how” and the “why” of what I write. Do I want thousands and tens of thousands to buy my books? Sure. But if that was the goal, I would not be writing the kinds of books I write.

And while the number may matter to a publisher, the number of readers doesn’t, in the end, matter. Wonders can be worked with one or two as with 400, or 10,000. We write to tell a story; what happens to that story is someone else’s business.

Top photograph: Southwark Cathedral, with the office building known as “The Shard” in the background.

The kidnapper was a man named

The kidnapper was a man named  In 2012, in a conversation with my publisher about writing life after A Light Shining, I mentioned this story. A few days later, he sent me a press story from England. A small pedophile ring had been uncovered within the Church of England. He wanted to know if I had “pre-written history.”

In 2012, in a conversation with my publisher about writing life after A Light Shining, I mentioned this story. A few days later, he sent me a press story from England. A small pedophile ring had been uncovered within the Church of England. He wanted to know if I had “pre-written history.”

The manuscript carcass – what was left over – had piled up. The publisher suggested a sequel. Out came the metaphorical ax again and chopped off about 65,000 words. Because of changes in Dancing Priest during the rewriting and editing process, those 65,000 words had to be reworked even more than the first manuscript. The story grew.

The manuscript carcass – what was left over – had piled up. The publisher suggested a sequel. Out came the metaphorical ax again and chopped off about 65,000 words. Because of changes in Dancing Priest during the rewriting and editing process, those 65,000 words had to be reworked even more than the first manuscript. The story grew. So

So