It was a conversation that went much like you might expect.

“I don’t understand it,” the executive said. “They hate us. They hate what we do. They don’t even really understand what it is that we do. They don’t understand how important our products are for farmers and for the world’s food supply.”

I was sitting in the executive’s office, working with him on a speech he was to give. What he was talking about wasn’t the subject of the speech, but it was clearly on his mind. I listened to what was essentially a rant, and then I asked a question.

“Have you read Wendell Berry?”

He stared at me. “Who’s that?”

And there it was. The animosity about the company’s products, the position of the company in the marketplace, the company’s close identification with “Big Agriculture,” and the executive’s being perplexed with the activists and animosity on social media could all be summed up that that question – “who’s that?”

I answered his question. “Berry,” I said, “is the man who has articulated a very different understanding of agriculture, the idea of community, and the understanding of the land. He’s widely read and admired. You have to read his essays to understand what’s behind all the animosity and controversy. His fiction and poetry will help, too.”

The response? “I don’t have time to read that stuff.”

Now 91, Berry was born in Henry County, Kentucky, where his family had farmed for five generations. He worked as a writer for agricultural publications like Rodale Press, but he eventually returned to Henry County and worked his own farm, Lane’s Landing.

But he continued to write. He wrote essays, poems, general interest articles, short stories and novels. He fictionalized his region of Kentucky, renaming the nearby town of Port Royal as “Port William.” Slowly and then rapidly, his ideas of land, community, and agriculture permeated American culture, influencing people like Joel Salatin and Michael Pollan, who in turn have had a huge influence.

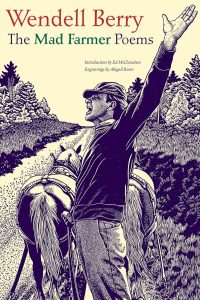

I generally prefer Berry’s fiction and poetry to his essays. A good place to start is with The Mad Farmer Poems, where Berry articulates his major problems with agriculture as practiced in the United States. It’s a relatively short collection, about the size of a chapbook, and it includes such poems as “The Mad Farmer Revolution,” “Manifesto: The Mad Farmer Liberation Front” (which is not as radical as it sounds) and “Prayers and Sayings of the Mad Farmer.”

The poems introduce you to a man who is, yes, angry about the state of modern agriculture, but who maintains a reverence for the land, the people who farm it, and the community the people create together. This is what Berry sees as broken and lost in America of the 21st century, and it’s difficult not see the sense he makes.

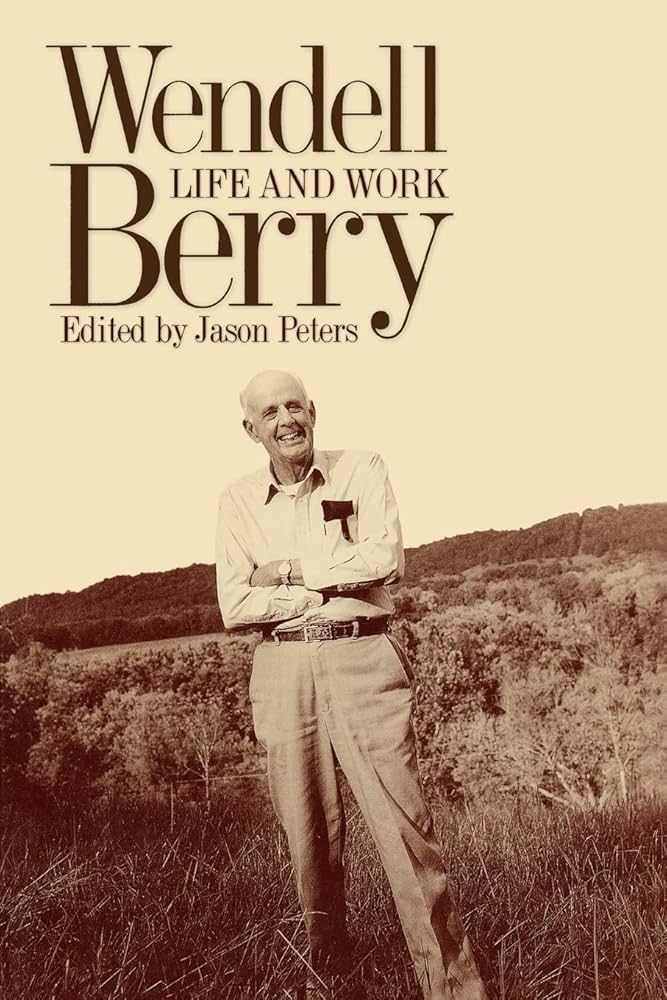

In 2007, Jason Peters, a professor at Hillsdale College, assembled and edited a collection of essays about Berry under the title Wendell Berry: Life and Work. It’s a good introduction to Berry and his writings from people who admire his work and his beliefs and have generally been strongly influenced by him.

The contributors include non-fiction author Sven Birkerts, novelists Barbara Kingsolver and Gene Logsdon, poets Donald Hall and John Leax, Patrick Deneen of Georgetown University, ecology writer Bill McKibben, and numerous others. They speak to Berry’s fiction, his poems, his faith, his philosophy, his deep beliefs in land and community, and related topics. And the key here is the word “related.” Berry doesn’t compartmentalize different parts of his life. It is all part of an integrated whole.

Berry received B.S. and M.A. degrees from the University of Kentucky. He was a Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford University and studied in Italy and France under a Guggenheim Fellowship. He taught at New York University and the University of Kentucky and served as a writer for Rodale Press. Since 1965, he and his wife have lived at Lane’s Landing. And he has a new Port William novel publishing in October – Marce Catlett: The Force of a Story.

When the executive and I had that conversation, more than a decade ago, I had read much of Berry’s poetry, two of his novels, and several of his essays – a mere drop in the bucket of what the man has published. I’ve read much more since then. And I think my answer to “Who’s that?” is even more on point now then it was back then. If you want to understand the culture – and cultural battle – of American agriculture, you have to read Wendell Berry.

Related:

My review of Berry’s That Distant Land.

My review of Berry’s Jayber Crow.

Wendell Berry and This Day: Poems at Tweetspeak Poetry.

Wendell Berry and Terrapin: Poems at Tweetspeak Poetry.

Wendell Berry’s Our Only World.

The Art of the Commonplace by Wendell Berry.

Nathan Coulter by Wendell Berry.

Andy Catlett: Early Travels by Wendell Berry.

A World Lost by Wendell Berry.

A Place on Earth by Wendell Berry.

The Memory of Old Jack by Wendell Berry.

Poets and Poems: Wendell Berry and Another Day.

Top photograph by Megan Andrews via Unsplash. Used with permission.