The Dancing Priest novels seem to be back in the fiction-becomes-fact business.

Last week, after saying he would not resign, Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby did, in fact, resign. This followed the release of the Makin Report, which documented the failings of the Church of England (COE) in a cover-up of an abuse scandal. The scandal went back to the 1980s when a barrister named John Smyth abused young teens at COE church camps, slipped out of England when it appeared the law was onto him, and went on to victimize more boys in Zimbabwe and South Africa.

Welby’s sin: he learned about the abuse in 2013 but failed to report it to authorities. Smyth could have been brought to justice at that time; he died in 2018.

One as-of-yet-unanswered question is if Welby was the only COE official to know. It’s unlikely that others, including people high in the hierarchy, also didn’t know. The scandal may not be over. And lest we think this type of scandal only happens to the big established denominations like the Church of England or the Roman Catholic Church, there are lessons here for all of us. A church I’ve attended had a member of the staff get involved in an inappropriate and illegal relationship; the difference was that the head pastor, as soon as he was told, called the police. That’s how it’s supposed to work, no matter how damaging it might be to an organization’s reputation. Righteousness trumps reputation, as Bernard Howard wrote for the Gospel Coalition.

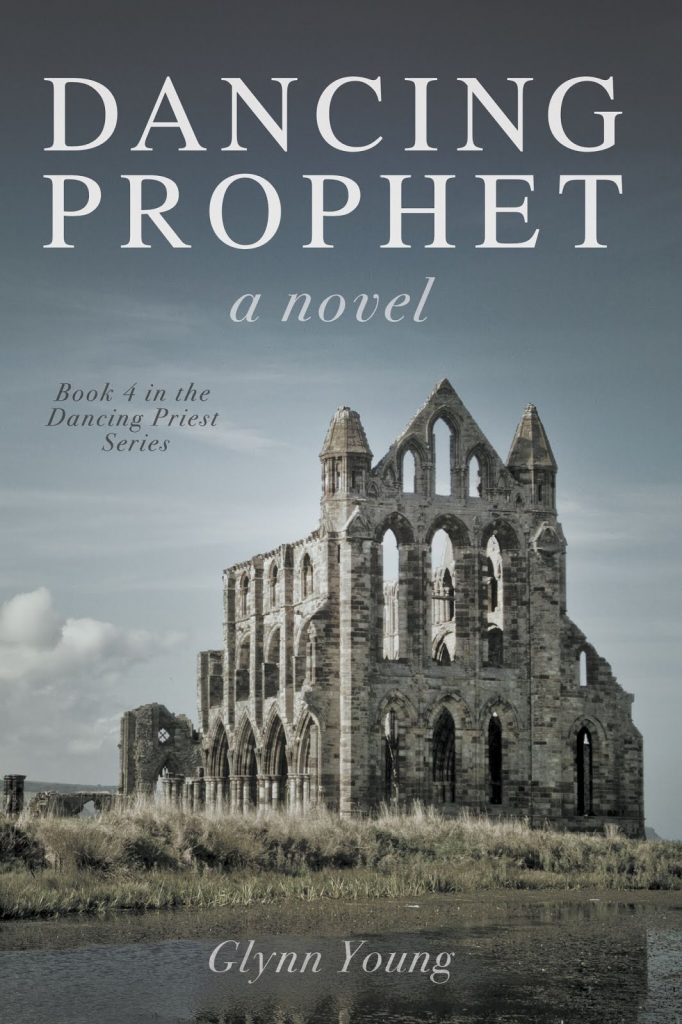

In Dancing Prophet (2018), the fourth of the Dancing Priest novels, Michael Kent-Hughes has an abuse scandal thrust upon him. He’s a former COE priest and now the king, and he’s simultaneously dealing with a developing church scandal and a collapse of the government of Great London. His church nemesis is the Archbishop of Canterbury, Sebastian Rowland, who has spent considerable time covering up an abuse scandal that threatens to blow the church apart.

During the research for the book, I learned that the Archbishop of Canterbury, along with the rest of the hierarchy and the church itself, is subject to the monarch. That’s how Henry VIII set it up in the 1530s during the English Reformation. And the archbishop functions at the pleasure of the monarch. That the current prime minister, Keir Starmer, refused to back Justin Welby publicly was of less importance than the silence that was coming from King Charles. Welby’s announcement noted that King Charles has graciously accepted his resignation. That’s how it works. The Catholic pope tells God and the church; the Archbishop of Canterbury tells the king (or the king asks for it).

In Dancing Prophet, Michael tells Sebastian Rowland he must resign. Rowland at first refuses, until Michael, in the presence of the police, explains the evidence against the archbishop, all of which will be made public. It’s worth noting, too, that Michael went to the police as soon as he became aware of the activities of one priest, which would soon explode into a global crime. And Michael, when he speaks to the British people, will tell them that the Church of England may not survive. Righteousness trumps reputation.

Dancing Prophet was written long before the John Smyth scandal was known publicly. What I did know concerned a COE abuse scandal involving some priests; it had first surfaced in the news in 2012. For the novel, I adapted the abuse scandal that has rocked (and continues to rock) the Roman Catholic Church to the COE.

I’m not a prophet; I can’t and don’t predict the future. But I’ve learned that, when you’re doing research for a book like any of the Dancing Priest novels (“future history,” one reader called them), you pick up on issues, concerns, trends, and ideas that are being discussed. You read about past events and troubles. You learn how people, especially people in authority, respond to what they see as threats. And you know what humans naturally tend to do: wish it would all go away, ignore it, make it worse, try to contain it, or cover it up. It might work for a time, but it usually doesn’t work forever.

We forget that lesson: righteousness trumps reputation.

Related:

Can Fiction Predict the Future?

Did Dancing Prophet Become Prophetic?

Top photograph by Ruth Gledhill via Unsplash. Used with permission.