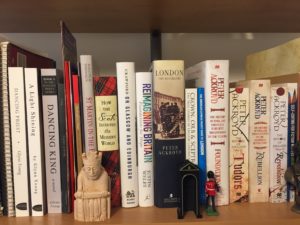

For roughly 14 months, from September 2005 to November 2006, a story idea that had been in my head for four years began to pour out on the computer screen. Once it came, it gushed, some 250,000 words of the roughest sort of rough draft. It would be spliced, diced, rewritten, divided into three parts, added to, and subtracted from, eventually published as Dancing Priest (2011), A Light Shining (2012), and Dancing King (2017), the three novels in the Dancing Priest series.

In November 2006, I stopped, and rested. Two months later, a story from my small suburban town of Kirkwood in metropolitan St. Louis became international headlines. A boy kidnapped in nearby Franklin County had been found by police in Kirkwood. With him was found a boy kidnapped in 2002.

The kidnapper was a man named Michael Devlin, a manager at a local pizza parlor. He had kept both boys at his apartment, on the far east side of Kirkwood and across the street from the town of Oakland. The apartment complex was just north of the trailhead for Grant’s Trail, which I had ridden hundreds of times. Which meant I had ridden past that apartment hundreds of times. I likely had seen the older boy, who after a couple of years had been allowed outside to ride his bike.

The kidnapper was a man named Michael Devlin, a manager at a local pizza parlor. He had kept both boys at his apartment, on the far east side of Kirkwood and across the street from the town of Oakland. The apartment complex was just north of the trailhead for Grant’s Trail, which I had ridden hundreds of times. Which meant I had ridden past that apartment hundreds of times. I likely had seen the older boy, who after a couple of years had been allowed outside to ride his bike.

This was, and is, every parent’s nightmare. Your child is taken, and you don’t know if the child is dead, abused, or raised as someone else’s child.

I didn’t feel personal responsibility. I felt something else: a deep sense of horror at a great evil happening a few yards away from where I regularly rode my bicycle.

I did the only thing I knew to do. My writing rest came to an end.

I didn’t write the story of Michael Devlin. Instead, I poured the horror of that story into fiction. Some 40,000 words later, I felt I could stop. I had dropped any reference to Devlin or even a character like him. I had moved the story to England. I moved the crime within the Church of England, most likely being influenced by all of the revelations from the Catholic Church in the United States. I added seminary connections.

And then I set the story aside. It had done what it needed to do. It was a kind of exorcism of the horror represented by Michael Devlin and what he had done.

In 2012, in a conversation with my publisher about writing life after A Light Shining, I mentioned this story. A few days later, he sent me a press story from England. A small pedophile ring had been uncovered within the Church of England. He wanted to know if I had “pre-written history.”

In 2012, in a conversation with my publisher about writing life after A Light Shining, I mentioned this story. A few days later, he sent me a press story from England. A small pedophile ring had been uncovered within the Church of England. He wanted to know if I had “pre-written history.”

In late 2017, I returned to the story and began to work it over. It grew; new elements and characters were added. The abuse story remained at the center; two additional story lines were added – one about a city government collapse and the other about a mother showing up after eight years. Only when the draft was done in early July did I realize that this had become a story about the collapse of institutional authority – family, church, government. It was exactly the institutions that Michael Kent-Hughes, the hero of Dancing King, had committed himself to during his coronation ceremony.

I’m not sure why I chose to develop the original manuscript into a full-blown novel. But I did. It was a story that was never intended or imagined to be written, but it was, because of the shock of a hometown horror.

The manuscript is now in the hands of the publisher for consideration.

Top photograph by Warren Wong via Unsplash. Used with permission.

The manuscript carcass – what was left over – had piled up. The publisher suggested a sequel. Out came the metaphorical ax again and chopped off about 65,000 words. Because of changes in Dancing Priest during the rewriting and editing process, those 65,000 words had to be reworked even more than the first manuscript. The story grew.

The manuscript carcass – what was left over – had piled up. The publisher suggested a sequel. Out came the metaphorical ax again and chopped off about 65,000 words. Because of changes in Dancing Priest during the rewriting and editing process, those 65,000 words had to be reworked even more than the first manuscript. The story grew. So

So

In August 2004 I started biking, which meant Michael started biking, too. Except he was training for the Olympics. Michael and I had a lot of conversations on various

In August 2004 I started biking, which meant Michael started biking, too. Except he was training for the Olympics. Michael and I had a lot of conversations on various  Michael Kent-Hughes had serious doubts. He occupies a leadership role that he’s not sure he’s at all qualified for. He knows what he’s been called to do, and it’s daunting. He finds himself the object of personal and institutional attacks. And he learns he has to depend upon people, and how much of his success depends upon finding good people to work for him.

Michael Kent-Hughes had serious doubts. He occupies a leadership role that he’s not sure he’s at all qualified for. He knows what he’s been called to do, and it’s daunting. He finds himself the object of personal and institutional attacks. And he learns he has to depend upon people, and how much of his success depends upon finding good people to work for him.